The role and task of Residential Child Care – there is no such thing as a ‘children’s home’ only children’s homes

This is raised as an area for focus in the Case for Change.

NCERCC has continuously provided material addressing this question.

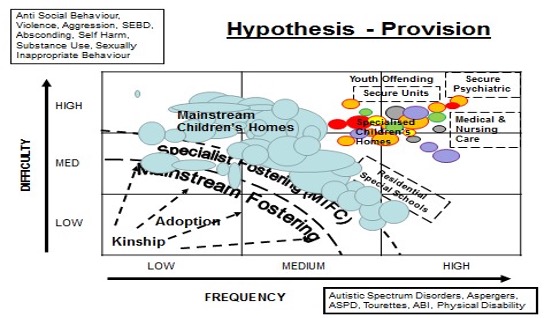

What is immediately apparent in the diagram below is that there is a diversity of needs, and so a diversity of response.

There is no such thing as a children’s home, as a singular typology, only children’s homes, a plurality.

Children’s homes meet many needs and take many forms, from a temporary refuge to a long-term alternative to family life to a therapeutic setting where children can seek to resolve problems caused by adverse life experiences.

There is a range or should there be a range of residential care models to meet different needs

Recognition of the full range of needs is required.

Often children in care are discussed as having uniform needs requiring generic services and settings provided according to a set schedule or specification for which a unit cost is applied.

Children are not units, nor are children’s homes ‘units’.

Recognition of individual histories and current needs requires a differentiated responses made according to difficulty and frequency. (If applying a market perspective it follows that there is not one market but many small specialist ones).

Any simplification should be resisted, and sophistication must be sustained.

Each of the following groupings of the needs of children in care identify a specialist need and response.

- Children with relatively simple or straightforward needs who require either short-term or relatively ‘ordinary’ substitute care

- Children or families with deep rooted, complex, or chronic needs with a long history of difficulty and disruption, including abuse or neglect requiring more than simply a substitute family

- Children with extensive, complex, and enduring needs compounded by very difficult behaviour who require more specialised and intensive resources such as a therapeutic community, an adolescent mental health unit, a small ‘intensive care’ residential setting or a secure unit.

Thinking of Residential Child Care, we should expect to see as Ann Davis observed in ‘The residential solution’ (1981) 3 roles and functions – supplemental, substitute, and alternative.

This is the reality of generations.

In recent discussions there is a discernible shift and general agreement that there are occasions when Residential Child Care can be helpful, using DfE research – safety, specialism, and choice.

There needs to be recognition that a young people do express a preference for residential care to any form of family care.

There needs to be recognition that when a young person can feel threatened by the prospect of living in a family or needs respite from it.

There needs to be recognition that having multiple potential adult attachment figures might forestall a young person from emotionally abandoning his or her own parents

There needs to be recognition that some children benefit from having available a range of carers

There needs to be recognition the emotional load of caring for children whose needs are characterised by high levels of complexity frequency for attentive this can be best met by being distributed among a number of carers.

The diversity of the sector, its range and specialism, can be glimpsed by the following broad current types of residential care provision

- Short-break children’s home – provides care for children with a disability to allow children, carers, and families to ‘take a break’.

- Short-term children’s home – provides time-limited care for a few days or weeks. A child may be placed because of unforeseen difficulties or a crisis because they are waiting for a longer-term placement to become available, or because they are waiting for an assessment.

- Long-term children’s home – provides care for a child for a substantial period, possibly until the child reaches adulthood.

- Children’s home for children with disabilities – provides specialised long- term care that can offer care, education, and health needs, often in one place.

- Residential special school – for children with SEN, providing education and addressing children’s disabilities and/or social, emotional, psychological, and behavioural needs.

- Therapeutic Community for children and young people – provides a participative, group-based approach to treat issues such as mental illness, attachment disorder and drug addiction.

- A secure children’s home – a specialist residential resource offering care, education, assessment, and therapeutic work. These are the only children’s homes allowed to lock doors to prevent children leaving or absconding.

England’s short term and last resort use of Residential Child Care is not the international experience

In 2007 and 2008 published 2013 DfE (then DCSF) funded research into how entry to public care for young people (aged 10 or over) could be either prevented, or planned and supported, through support for young people and their families (very like the Care Review today). It examined local and national policies in Denmark, France and Germany compared to England. See ‘Working at the ‘edges’ of care? European models of support for young people and families’ for a more detailed research summary

The findings included the following

- Denmark, France, and Germany all had a greater proportion of children looked after away from home than does England. There was no clear evidence from the interviews that thresholds for care entry were lower in other countries than in England.

- Young people in the care system in England are not a homogenous population. Young people aged 10-15 years form quite diverse groups and there are important differences between those who enter care for the first time (aged between 10-15) and those who re-enter at this age with a previous history of care.

- Research in all the countries highlighted the potential for therapeutic approaches to support young people and families to prevent out-of-home placement.

- The continental European countries appeared to have a wider range of options when children did need to live away from home, which included part-time, respite and shared-care arrangements. Innovative models were found in England too, but the study highlighted a need to develop further a differentiated array of placement choices.

- In all four countries, interviewees emphasised the importance of engaging young people and their families in the process of planning for placement.

- The workforce supporting children and families in the other European countries had higher levels of qualification than in England.

Reading this today one reels with the staggering loss of the loss of the social ecology of the responses to children, and especially in the Residential Child Care sector.

The need for more, differentiated, residential options is clear, not only intensive and specialist we have now but recovering some to the other group living settings we had in other times.

What stops this thinking?

- The English approach to thinking about Residential Child Care is as an intervention defined by a risk perspective rather than what services best meet the outcomes and needs of children and families.

- Residential Child Care is seen as separate from children’s services, which themselves predominantly have increasingly taken the focus of protection and safeguarding.

- This is a different focus from creating a facilitating environment. Creating and sustaining individual and community resilience is less of a focus than interventions to mitigate or remove risk when resilience has become thinned.

(Expanded from comments by Lisa Holmes Rees centre

https://www.communitycare.co.uk/2019/11/15/using–algorithms–childrens–social–care–experts–call–betterunderstanding–risks–benefits Accessed 04 12 19)