Knowledge Transfer: Keeping Your Moral Compass Under Pressure

A big thank you to Community Care and to Sara Harper, Service Manager at a London-based VAWG organisation, who wrote the article

NCERCC has made only a few amendments to make its contents relevant to RCC.

Defining moral suffering

Residential Child Care workers will recognise moral suffering when defined as a form of work-related psycho-emotional harm that may occur when we know the correct moral outcome of a significant event but are unable to achieve it or forced to accept the wrong one (Papazoglou and Chopko, 2017; Harper and Karypidou, 2024).

An example in Residential Child Care might be a decision made about a child by a social worker, to move before readiness and resilience was established. There is a dissonance between actions and values, a conflict in the individual that eventually can destabilise moral code and cause feelings as guilt, shame, and disillusionment

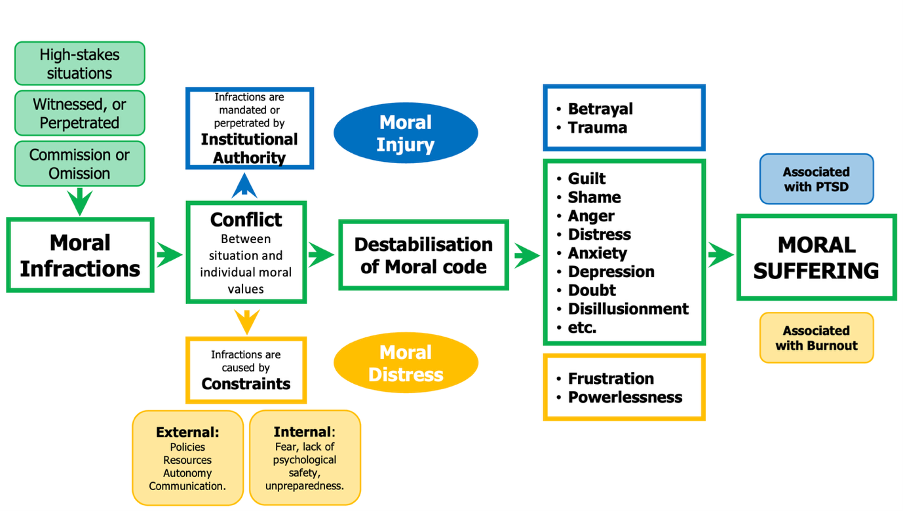

This figure in the Community Care article shows this well.

The progression of moral suffering (green) following moral infractions, including dimensions of moral injury (blue) and moral distress (yellow). From Harper and Karypidou (2024), based on conceptualisations by Sugrue (2019), Mänttäri-van der Kuip (2020) and British Medical Association (2021).

Dimensions and effects

Two dimensions of moral suffering are:

- Moral distress: the event is caused by constraints that prevent the morally correct action (Sugrue, 2019). This is characterised by feelings of frustration and powerlessness and associated with burnout.

- Moral injury: the event is directed by a figure of institutional authority or by oneself (Shay, 2014). This is characterised by feelings of betrayal and transgression and associated with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Moral suffering can manifest as:

- Inward harm: impaired function, mental health issues, changes in self-identity and world view, wounds and threats to moral integrity

- Outward harm: social and professional issues (e.g. anger, avoiding interactions with clients, negative impact on care, frequent thoughts about quitting) (Harper and Karypidou, 2024).

Constraints

Constraints are elements that prevent a morally correct outcome, including institutional barriers, both internal and external.

| External | Internal |

| Time pressure |

Lack of psychological safety (i.e. an environment that allows workers to feel safe in speaking up and raising concerns) (Campbell, 2025) |

| Heavy caseloads | Lack of preparedness (i.e. lack of appropriate preparation to face up to the challenges of the job) |

| High levels of job stress | |

| Inappropriate policies | |

| Issues with communication | |

| Lack of funding, resources, effectiveness, decision-making autonomy |

Where there is inability to cope and resolved by caring for the self (e.g. self-care) (World Health Organization, 2019), moral suffering broadens the view from individual to systemic, including institutional constraints among the roots of occupational distress.

Moral suffering is the response to a threat to one’s morality (Williamson et al, 2021). Thus, the treatments and strategies used to manage burnout and PTSD may be insufficient in addressing moral suffering, as neither considers the moral wounds that may occur when clashing with systemic constraints (Dean et al, 2019).

Harper and Karypidou, 2024, studing social care workers found that approximately 1 in 3 participants were experiencing dimensions of moral suffering.

- 9% reported moderate-to-high levels of moral distress, including having to work in ways that contravene one’s values and better judgement, being impeded by rules and regulations, and feeling unable to perform to one’s standards

- 3% reported moderate-to-high levels of moral injury, including witnessing and perpetrating transgressions of one’s moral values, and feeling betrayed by leaders and institutions.

Risk to social workers

There is a firm moral imperative of caring for others at the core of RCC, its guiding principles are rooted in humanitarianism and social justice. There is a high degree of altruism for becoming a Residential Child Care Worker.

Secondary and vicarious trauma come with the Residential Child Care role and task, some from the very act of care, some from the needs and wishes of children, statutory requirements, political and administrative policies, budgetary and resource constraints. These affect our own moral compass and wellbeing (Ylvisaker and Rugkåsa, 2021). Our guiding principles are at significant risk of experiencing moral suffering (Janssen, 2016) often by constraints that are outside of our control. However, there are steps and protective factors to help reduce its impact.

Knowledge is power

At a personal level – building awareness reduces stigma and increases the likelihood of individuals disclosing distress and seeking support early (Henderson et al, 2017), including through regular debriefing and mental health days (Hancock et al, 2020).

On a larger scale – awareness can both increase political attention and investment and foster greater empathy and understanding in the workplace (Knight, 2024).

Building moral resilience

Moral resilience has been defined as ‘the capacity of an individual to preserve or restore integrity in response to moral adversity’ (Rushton, 2023). Some key factors are:

- Reflective practice and self-examination: shifting focus inwards and exploring who we are, our core moral principles, and how we will respond to moral dilemmas in a way that aligns with our higher guiding values (Rushton, 2023; Bedzow, 2025)

- Transformation over restoration: accepting and reframing moral challenges as tools to adapt, rather than struggling to return to before the moral challenge occurred

- Intentionality and empowerment: finding, within the flow of uncontrollable events, those elements that can be acted on based on one’s core principles, restoring purposefulness and agency, and finding ‘meaning amid adversity’ (Rushton, 2023). In a nutshell, making individual and professional moral principles an explicit point of reflection, development, and conversation can help prepare for – and adapt to – the moral challenges inherent to the social work profession.

- Fostering empathy, respect, understanding, and cooperation among colleagues can help build psychological safety and a supportive environment. This, in turn, has a direct effect on moral suffering (Hancock et al, 2020; Webber et al, 2021; Sumanth et al, 2024). Doing whatever possible to acknowledge each other’s challenges and good work, building collaborative and empowering relationships, and speaking openly about the moral complexities of the profession contribute to a more ethical and caring culture, which can be cultivated at any organisational level (Webber et al, 2021; Li et al, 2022).

Cultivating protective factors

Social-emotional competency – e.g. emotion regulation, introspection, emotional literacy, and empathic communication – has been shown to reduce job stress (Kinman and Grant, 2011), a factor in moral suffering. Similarly, research indicates that developing competence in ethical decision-making (i.e. making choices that factor in ethical implications) reduces the impact of moral suffering (Hwu and Pai, 2024). Finally, experience, training, and length of tenure (i.e. years on the job) have been implicated as protective factors (Hubbell et al, 2024), suggesting that the impact of moral suffering may lessen the more experience one acquires on the job.

For leaders

Any measures that can realistically be put in place to reduce internal and external constraints should be implemented to reduce the negative effects that moral suffering has on workers and (indirectly) on clients. While many constraints may be out of reach, there are still steps a leader can take, starting with creating an environment where workers are able to cultivate the points above. Practicing inclusive leadership (i.e. being available, transparent, constructive, and attuned to workers’ needs) and fostering a supportive, empowering, collaborative, and ethical climate through policies, training, and general culture, are ways to build preparedness and psychological safety and reduce emotional exhaustion (Li et al, 2022). Finally, acknowledging the moral challenges inherent to Residential Child Car and providing forums for these to be examined and to reflect on individual and professional ethical principles can help build moral resilience (Thomas et al, 2021).

A big thank you to Sara Harper MSc MBPsS, Service Manager at a London-based VAWG organisation

References

Bedzow I (2025) A framework for coping with moral challenges.

https://www.capc.org/documents/download/853/ (accessed 19 September 2025)

Bisman C (2004) Social work values: the moral core of the profession. British Journal of Social Work. 34(1):109–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bch008

British Association of Social Workers (2021) Code of Ethics. https://basw.co.uk/policy-practice/standards/code-ethics (accessed 19 September 2025)

British Medical Association (2021) Moral distress and moral injury. Recognising and tackling it for UK doctors. https://www.bma.org.uk/media/4209/bma-moral-distress-injury-survey-report-june-2021.pdf (accessed 19 September 2025)

Campbell Y (2025) The ethical responsibility of psychological safety: Leadership at the intersection of safety culture. Healthc Manage Forum. 8404704251348817. https://doi.org/10.1177/08404704251348817

Dean W, Talbot S, Dean A (2019) Reframing clinician distress: moral injury not burnout. Fed Pract. 36(9):400-402

Hancock J, Witter T, Comber S et al (2020) Understanding burnout and moral distress to build resilience: a qualitative study of an interprofessional intensive care unit team. Can J Anaesth. 67(11):1541-1548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-020-01789-z

Harper S, Karypidou A (2024) Moral suffering in frontline social care workers: a study of moral injury and moral distress. European Journal of Mental Health. 19:e0021. https://doi.org/10.5708/EJMH.19.2024.0021

Henderson C, Robinson E, Evans-Lacko S, Thornicroft G (2017) Relationships between anti-stigma programme awareness, disclosure comfort and intended help-seeking regarding a mental health problem. Br J Psychiatry. 211(5):316-322. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.116.195867

Hubbell SL, Young SE, Duea SR, Prentice CR (2024) Identifying protective factors related to burnout, moral injury, and resilience of registered nurses: An exploratory analysis. Mental Health Science. 2(3):e71. https://doi.org/10.1002/mhs2.71

Hwu LJ, Pai HC (2025) The moral distress, protective factors, and resilience: the role of ethical decision-making competence among student nurses. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 30(4):1217-1230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-024-10399-z

Janssen JS (2016) Moral distress in social work practice: when workplace and conscience collide. https://www.socialworktoday.com/archive/052416p18.shtml (accessed 19 September 2025)

Knight Kinman G, Grant L (2011) Exploring stress resilience in trainee social workers: the role of emotional and social competencies. British Journal of Social Work. 41(2):261–75. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcq088

A (2024) Why mental health awareness matters. https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/explore-mental-health/blogs/why-mental-health-awareness-matters (accessed 19 September 2025)

Li X, Peng P (2022) How does inclusive leadership curb workers’ emotional exhaustion? The mediation of caring ethical climate and psychological safety. Front Psychol. 2022 Jul 7;13:877725. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.877725

Mänttäri-van der Kuip M (2020) Conceptualising work-related moral suffering—exploring and refining the concept of moral distress in the context of social work. British Journal of Social Work. 50(3):741–757. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcz034

Papazoglou K, Chopko B (2017) The role of moral suffering (moral distress and moral injury) in police compassion fatigue and PTSD: an unexplored topic. Front Psychol. 8:1999. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01999

Petersén AC (2022) New insights on motives for choosing social work as a career: answers from students and newly qualified social workers. Social Work Education. 43(3):1–15

Rushton CH (2023) Transforming moral suffering by cultivating moral resilience and ethical practice. Am J Crit Care. 32(4):238-248. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2023207

Shay J (2014) Moral injury. Psychoanalytic Psychology. 31(2):182–91. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036090

Skovholt TM (2005) The cycle of caring: a model of expertise in the helping professions. Journal of Mental Health Counseling. 27(1):82–93

Sugrue E (2019) Understanding the effect of moral transgressions in the helping professions: In search of conceptual clarity. Social Service Review. 93(1):4–25. https://doi.org/10.1086/701838

Sumanth JJ, Hannah ST, Herbst KC et al (2024) Generating the moral agency to report peers’ counterproductive work behavior in normal and extreme contexts: the generative roles of ethical leadership, moral potency, and psychological safety. J Bus Ethics. 195:653–680. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-024-05679-y

Thomas T, Kumar S, Davis FD, Thammasitboon S (2022) Key insights on pandemic moral distress: role of misaligned ethical values in decision-making. Crit Care Med. 50(1):262. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ccm.0000808492.62215.d4

Webber J, Trothen TJ, Finlayson M, Norman KE (2022) Moral distress experienced by community service providers of home health and social care in Ontario, Canada. Health Soc Care Community. 30(5):e1662-e1670. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13592

Williamson V, Murphy D, Phelps A, Forbes D, Greenberg N (2021) Moral injury: the effect on mental health and implications for treatment. Lancet Psychiatry. 8(6):453-455. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00113-9

World Health Organization (2019) Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon”: International classification of diseases. https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases (accessed 19 September 2025)

Ylvisaker S, Rugkåsa M (2021) Dilemmas and conflicting pressures in social work practice. European Journal of Social Work. 25(4):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2021.1954884